Do We Have Enough Doctors in India? 🤔

Exploring India’s Doctor Shortage: Causes, Global Comparisons, and Possible Solutions

India is a land of over 1.4 billion people, making it one of the most populous countries in the world. But when it comes to healthcare, one fundamental question stands out — Do we have enough doctors?

The short answer is no. The longer answer, however, reveals a complex story of numbers, policy failures, and even opportunities for improvement.

Let’s dive into the details.

The Doctor-to-Population Ratio 👨⚕️👩⚕️

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the ideal doctor-to-population ratio should be 1 doctor /1000 people.

However, India's situation is far from ideal. As per the National Health Framework (NHP) 2022, India has approximately 1 doctor for every 1,511 people. That's better than a decade ago. But it is still significantly reduced compared to many developed countries.

(Source: National Health Profile 2022, WHO Health Workforce Statistics)

While claiming that there is no shortage of doctors in the country, Pawar told the Rajya Sabha on July 26 that, "There are 13,08,009 allopathic doctors registered with the State Medical Councils and the National Medical Commission (NMC) as of June, 2022. Assuming 80% availability of registered allopathic doctors and 5.65 lakh AYUSH doctors, the doctor-population ratio in the country is 1:834 which is better than the WHO standard of 1:1000."

Why Does This Matter? 🚑

The shortage of doctors has a ripple effect throughout the healthcare system.

Long wait times, overworked professionals, and inadequate medical coverage in rural areas are just a few symptoms of the problem. And these issues aren’t just an inconvenience—they can be a matter of life and death.

In states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, where the population density is higher and health infrastructure is less developed, the shortage of medical professionals is even more acute.

What’s the WHO Standard, and Do AYUSH Doctors Count? 🤔

When we talk about whether India has enough doctors, a commonplace factor of reference is the World Health Organization (WHO) standard.

The WHO recommends 1 physician in keeping with 1,000 people as the precise doctor-to-populace ratio. This ratio ensures that fundamental healthcare needs are met, and people can access scientific specialists without immoderate delays.

In India, however, the cutting-edge ratio is about 1 doctor in step with 1,511 human beings—that is a long way from the correct.

Does This Ratio Include AYUSH Doctors? 🌿

In India, there is a unique factor to consider: AYUSH doctors.

These practitioners are trained in Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy, which are traditional forms of medicine.

India has about 800,000 AYUSH doctors, which plays a significant role, especially in rural areas where access to modern allopathic doctors is scarce.

But here's the catch—AYUSH doctors are not counted under the WHO doctor-patient ratio. The WHO standard refers specifically to allopathic doctors (MBBS-qualified practitioners), as it is based on the global availability of professionals trained in modern medicine.

The AYUSH Debate 🔄

While AYUSH doctors provide critical healthcare services, particularly in underserved areas, the debate over whether they should be counted as "doctors" under the allopathic healthcare system continues:

Supporters argue that AYUSH doctors provide essential primary care and alleviate the burden on the allopathic healthcare system. They are essential in rural regions where medical care is otherwise inaccessible.

Critics say that while AYUSH practitioners have their field of expertise, they do not receive the same training in modern medicine as MBBS doctors. Therefore, they shouldn't be counted in the same category as allopathic doctors when measuring healthcare coverage.

What’s Happening on the Ground? 🏥

Many AYUSH doctors fill the gap where allopathic doctors are in short supply. In some states, AYUSH practitioners are even integrated into government healthcare systems. However, from a WHO standard and policy perspective, India still needs to improve its ratio of allopathic doctors to meet global benchmarks.

State-Wise Distribution of Hospitals and Doctors 📊

This table provides an overview of the wide variety of hospitals and medical doctors (both in government and private sectors) in numerous states, accompanied via a rural vs. Urban breakdown.

The information emphasizes how states range significantly in healthcare infrastructure.

While we can says that most of the rural has very less exposure to doctors wben most of the population stays in rural areas.

To understand this in much deeper we can take a look at various global healthcare systems.

Comparing Global Healthcare Systems 🌍

Let’s take a look at how other countries manage their healthcare systems and the availability of doctors:

United States: Despite having a much higher ratio (1:370), healthcare in the U.S. remains expensive and often inaccessible for lower-income groups. The U.S. has plenty of doctors, but the system's inefficiencies lie in insurance and affordability.

United Kingdom: The UK's National Health Service (NHS) provides free healthcare to its citizens, and with a ratio of 1:357, it seems well-staffed. However, NHS doctors often report being overburdened, showing that even a good ratio doesn't solve all problems.

Germany: Germany has one of the best ratios at 1:269, with universal healthcare coverage and a strong emphasis on primary care, giving its population access to regular medical services. It's a model that many developing nations, including India, could learn from.

China: China’s ratio (1:1,400) is slightly better than India’s, but it also faces challenges in rural healthcare availability. Much like India, urban-rural disparity remains a significant issue.

Why India Struggles to Maintain Doctor Numbers? 💡

The scarcity of doctors in India stems from several intertwined reasons:

Insufficient Medical Colleges: Although India has over 660 medical colleges (as of 2022), they are insufficient to meet the enormous demand for healthcare professionals. Furthermore, these institutions are unevenly distributed, with many concentrated in urban areas.

Rural-Urban Divide: Rural areas house nearly 65% of India’s population, but only 27% of the country’s doctors serve these areas. The lack of basic amenities and infrastructure makes it unattractive for medical professionals to work in these regions.

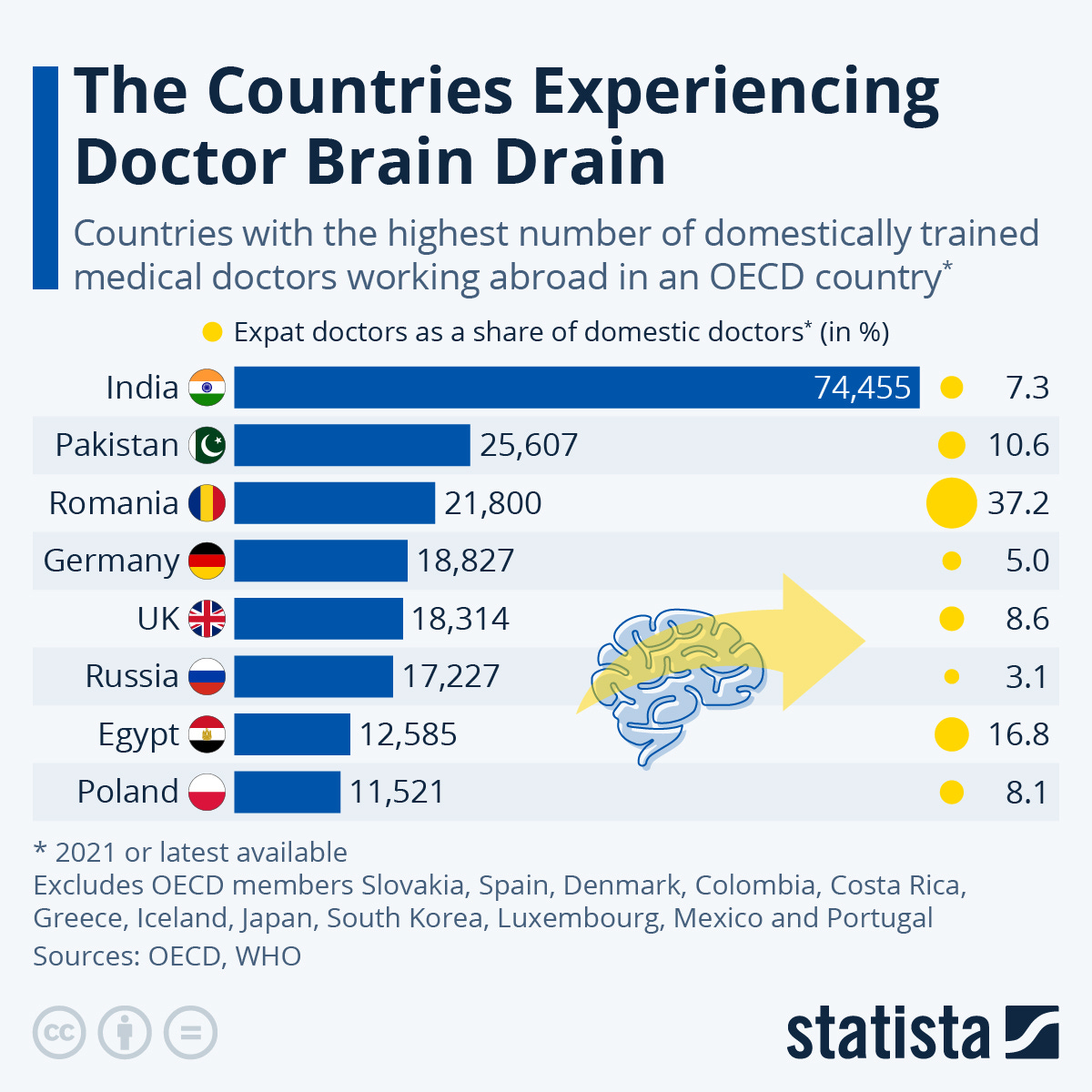

Brain Drain: Indian doctors are highly skilled, and many seek opportunities abroad, especially in countries like the U.S., UK, Canada, and Australia, which offer better salaries and working conditions. According to the OECD, India is one of the largest contributors of migrant doctors to the developed world, and as many as 60,000 Indian doctors are currently working overseas.

Brain Drain: A Major Culprit? 🧠

India’s loss is often the gain of the developed world.

Indian doctors abroad: Countries like the United States have thousands of Indian-origin doctors. 1 in 4 foreign doctors in the U.S. is Indian.

Financial motivation: Doctors in India can expect to earn anywhere from ₹8-15 lakhs annually in their early careers. In contrast, in the U.S., an Indian-origin doctor could earn more than $200,000 (₹1.6 crore) annually, a substantial financial incentive to emigrate.

Professional Growth: Countries abroad often offer better work-life balance, more advanced healthcare infrastructure, and opportunities for cutting-edge research, all of which are attractive to Indian doctors looking to expand their professional horizons.

This brain drain exacerbates India's doctor shortage and creates a vicious cycle: the more doctors leave, the harder it is for India to retain talent, leading to further overwork and under-resourced conditions.

How Can India Fix This? 💡

Improving the doctor-patient ratio in India will require both short-term fixes and long-term structural changes. These cannot be fixed in a hurry and needs a deep action to take.

Increasing Medical Seats: India has been ramping up the number of medical colleges and postgraduate seats. According to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, the number of MBBS seats has increased from 50,000 in 2014 to 1,00,000 in 2023. This will help, but it's only part of the solution.

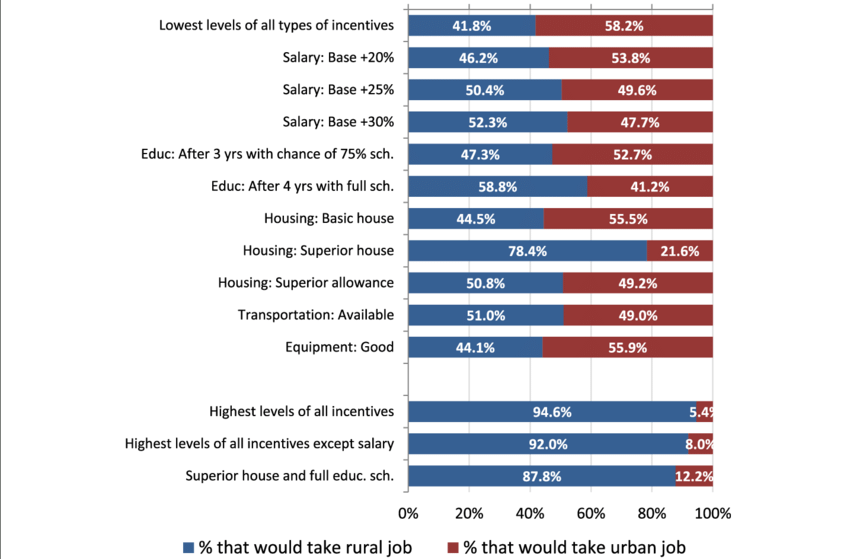

Bridging the Urban-Rural Divide: Incentives like better housing, allowances, and mandatory rural service can help ensure more doctors choose to practice in underserved regions

Retaining Talent: Tackling brain drain will require improving working conditions for doctors within India. Higher pay scales, better infrastructure, and research opportunities can help retain talent. Additionally, public-private partnerships could bolster India's healthcare system and create new pathways for professional growth.

Technology Integration: Telemedicine has been growing rapidly in India, with the government promoting platforms like eSanjeevani, which allows doctors to consult patients remotely. This can help address healthcare shortages in rural areas, particularly when in-person visits are not feasible.

Global Best Practices: India could learn from countries like Germany, where a focus on primary healthcare and a robust insurance model keeps doctor-patient interactions frequent and manageable. Investing in more healthcare personnel like nurse practitioners and community health workers can also help take the load off doctors.

How is the Indian Government Tackling the Doctor Shortage? 🏥

India’s shortage of doctors, especially in rural areas, is a critical issue, and the Indian government has launched several initiatives and policies to address this. From increasing the number of medical colleges to leveraging technology through telemedicine, here are some key policies and strategies aimed at solving the doctor shortage in India.

1. Ayushman Bharat – Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY) 🌍

The Ayushman Bharat initiative is one of the most comprehensive healthcare reforms launched by the Indian government. It includes two key components: Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) and Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY).

Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs): The government has committed to establishing 150,000 HWCs across the country by transforming existing sub-centers and primary health centers (PHCs). These HWCs will provide comprehensive primary care services, including maternal and child health services, non-communicable diseases, and essential drugs.

Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY): This scheme provides health coverage up to ₹5 lakhs per family per year for secondary and tertiary hospitalization to over 10 crore vulnerable families. By providing financial protection, it also aims to reduce the burden on public hospitals and enhance healthcare access, especially in rural areas.

This scheme reduces the cost barrier to accessing healthcare and helps rural populations by strengthening primary healthcare infrastructure.

2. Expansion of Medical Education 🎓

The government has focused on increasing the number of medical colleges and seats to boost the production of doctors in India. Here are some measures:

New Medical Colleges: The government has set a goal to establish one medical college for every three parliamentary constituencies and at least one medical college in each state. In 2020, the government approved the construction of 157 new medical colleges by 2025, a significant jump from the existing number.

Medical Seats Expansion: There has been a substantial increase in the number of MBBS and postgraduate (PG) seats across India. As of 2023, India has over 654 medical colleges offering around 101,043 MBBS seats and 52,720 PG seats. The government has also implemented policies to increase the number of AIIMS (All India Institute of Medical Sciences) institutions, with a target to have 24 AIIMS operational soon.

By increasing the number of medical colleges and seats, the government aims to produce more doctors, thereby addressing the demand-supply gap.

3. Compulsory Rural Service for Medical Graduates 🏞️

To address the shortage of doctors in rural areas, several state governments have implemented policies for compulsory rural service:

Mandatory Rural Posting: Medical graduates from public medical colleges are often required to complete a mandatory rural posting as part of their internship or residency. For example, states like Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra have made it compulsory for doctors to work in rural health centers for at least one year after completing their degrees.

Bond System: In some states, medical students are required to sign a service bond, which mandates them to work in rural areas for a fixed duration. If they choose not to fulfill this obligation, they have to pay a penalty.

This ensures that doctors are available to serve in underserved rural areas, albeit temporarily. Over time, this policy can improve rural healthcare access, though retention remains a challenge.

4. Incentives for Doctors in Rural Areas 💰

To encourage doctors to work in rural and remote areas, the government provides financial and non-financial incentives:

Higher Salaries: Doctors working in rural areas are often given higher salaries and allowances compared to those working in urban centers. This includes housing allowances, hardship pay, and additional perks.

Promotion and Career Advancement: Some states offer fast-track promotions and better career prospects for doctors who choose to work in rural or difficult-to-serve areas.

Infrastructure Improvements: By improving the working conditions in rural hospitals and health centers—such as better housing, security, and equipment—the government hopes to attract more doctors to serve in rural regions.

These incentives make rural postings more attractive, helping to retain doctors in underserved areas.

5. Strengthening Primary Healthcare Infrastructure 🏥

The government’s focus on strengthening primary healthcare centers (PHCs) and sub-centers (SCs) is crucial to improving healthcare delivery in rural areas.

Upgrading PHCs: PHCs are being equipped with better medical equipment and diagnostic tools, making them more effective in delivering healthcare services. The National Health Mission (NHM) focuses on improving the infrastructure of sub-centers and PHCs and ensuring that these facilities have the necessary resources, including doctors and paramedical staff.

Staffing PHCs: To address the shortage of doctors, the government is also deploying mid-level healthcare providers (MLHPs) like nurse practitioners and community health officers in PHCs to handle basic healthcare services.

Strengthening primary healthcare centers reduces the burden on secondary and tertiary hospitals and brings essential healthcare services closer to rural populations.

6. Telemedicine and Digital Healthcare 📱

Telemedicine has become a game-changer for rural healthcare, especially in remote areas where access to doctors is limited. The government has launched several initiatives to promote telemedicine:

eSanjeevani: The eSanjeevani telemedicine platform allows patients in rural areas to consult with doctors and specialists from urban centres through video calls. As of 2023, the platform had completed over 14 million teleconsultations.

Telemedicine Guidelines: In 2020, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) issued comprehensive telemedicine practice guidelines to promote its use across the country. This ensures that patients can access timely consultations without having to travel long distances.

Telemedicine bridges the urban-rural healthcare gap by connecting rural patients with doctors and specialists in real time.

7. Integration of AYUSH Practitioners in Rural Healthcare 🌿

Given the shortage of MBBS doctors in rural areas, the government has integrated AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy) doctors into the public health system:

Training AYUSH Doctors for Primary Care: AYUSH practitioners are often trained in basic primary care and are posted in PHCs and sub-centres, particularly in states where allopathic doctors are unavailable. They help reduce the patient load by providing first-contact healthcare services.

Collaborative Healthcare Models: In some states, AYUSH practitioners work alongside allopathic doctors to deliver comprehensive care, especially in rural areas where there is a lack of medical personnel.

This integration helps fill the gap in rural healthcare services, although AYUSH doctors primarily handle preventive care and basic treatments.

8. National Medical Commission (NMC) Reforms 🏛️

The establishment of the National Medical Commission (NMC) in 2020 replaced the Medical Council of India (MCI) with a more streamlined, transparent body for medical education and regulation. Key reforms include:

Simplifying Medical Education: The NMC has focused on streamlining the medical education system by standardizing medical curriculum and practices, making it easier to increase the number of medical seats.

Focus on Primary Healthcare Training: The NMC emphasizes training doctors in primary and preventive care, particularly for rural and underserved populations. It aims to create a more community-oriented workforce by including rural health training in the medical curriculum.

This reform ensures a more efficient medical education system, with a focus on producing doctors who can address India’s healthcare needs, particularly in rural areas.

Final Thoughts 💭

India has made some progress in addressing its doctor shortage, but there’s still a long way to go. Closing the gap will require substantial investment in healthcare infrastructure, medical education, and policies designed to retain medical talent within the country.

The government’s focus on initiatives like the Ayushman Bharat scheme, which promises universal health coverage, is a positive step. But for it to succeed, there must be enough doctors to provide that care in the first place.

If India can reduce its brain drain, incentivize rural service, and continue to boost medical education, it might just be able to heal the shortage — and by extension, the nation.

Hope you enjoyed reading this article.

If you found it valuable, hit a like ♥♥ and consider subscribing for more such content every week.

If you have any questions or suggestions, leave a comment.